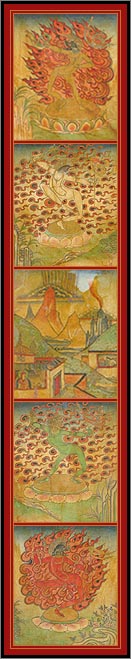

The Image:

A sidewalk café at sunset. In the background is a narrow, cobblestone

street on a canal lined with 15th-century European houses. Strangely

enough, over the rooftops of the houses, one can see the Himalayas

in the distance. In the foreground is a small round table, at which

are sitting two Tibetan monks and a bearded guy in a black leather

jacket. They appear to be singing.

It's the afternoon of my last full day in Amsterdam. I am doing what I do when I am in Amsterdam, which is surf. Don't laugh. Amsterdam is eminently surfable. Of course, it depends on what you surf. Folks who surf waves or snow would probably argue with my choice of locations.

But I surf polarities. And in my opinion, Amsterdam is the most polarized, and in that sense, the most Tantric city I have ever visited. The entire Centrum is a network of canals that are conduits for as much power as they are water, and the result is an energy vortex, a labyrinth of light that is as spectacular as Carrizo Gorge or any of the places of power we journeyed to with Rama.

But there is more variation of energy in Amsterdam, with completely contradictory energies coexisting alongside one another as peaceful neighbors. For example, one of the city's best spiritual bookstores is sandwiched between a coffee house whose menu offers more varieties of hashish than it does beer and the same city's most famous brothel. No one has any problem with this. Walking around, within a two-block radius you can experience a five-star hotel, the red-light district, one of the oldest Universities in Europe, a serious druggie district, and shops that make Rodeo Drive look like Wal-Mart.

So for someone like me, someone who gets off on the interplay of polarized energies, Amsterdam is a great place to surf. Plus, I don't need no steenkin' board, just my own two feet. I am putting them to use this particular afternoon, wandering as I usually do through the narrow streets. But today I also have work to do, so I am not exactly wandering at random. I am retracing steps I had taken a week ago while putting up posters.

I stop from time to time as I find one of them, plastered onto a wall full of other posters advertising lectures, concerts, raves, and whatever else is happening in Amsterdam this week. To be honest, our posters are among the classiest of the lot. They feature a full-color image of a Tibetan Buddha seated in lotus position and, both in Dutch and in English, an invitation to a free talk on meditation. Each of them cost us a couple of bucks each to print. Lovely as they are, each time I find one, I tear it down and stuff it into my shoulder bag. The free series is over, and the Rama students who came here to teach meditation for free are history.

In fact, I am the only one left. Most of the other guys blew town the day Rama left, and the last of them flew out this morning. This is my last night here as well, and I am just trying to spend a little time trying to clean up the karma in Dodge City before I catch the last stage out of town myself.

Suffice it to say our attempt to teach in Amsterdam did not work out exactly as planned. We met some lovely people, many of whom seemed genuinely interested in meditation, and invited over a hundred of them to two special meditations with Rama, in one of the nicest auditoriums in Amsterdam. It did not go well. Rama felt there was a lot of hostility in the audience, and after the second of the two nights, announced to the dozen or so of us who had been teaching in Amsterdam that he was shutting things down and was outa here, never to return.

So I'm wandering around today, pulling down the last of our posters, trying to leave no trace that we were ever here. It's somewhat of a poignant afternoon, because as I walk I am dealing with some internal stuff that I would have referred to, back in my hippie days, as heavy shit. Rama's reaction to the talks - the words he used when meeting with us afterwards - have set me thinking, for the first time in thirteen years, about leaving the study. It's not that what he said was that shocking or new, or that I think any less of him. It's just that in that small meeting, seated around a table at a late-night pizza parlor, I saw for the first time that my teacher's goals and mine no longer seemed to be the same, and that it might be time for me to move on.

So I'm walking along, lost in thoughts like this, when I turn the corner onto yet another narrow, cobblestone street and see the two Tibetan monks. They are fairly young, probably in their late twenties or early thirties, and are dressed in traditional red robes. Their heads are shaved and they are wearing no socks with their battered leather shoes, but they don't seem to be cold. I am wearing a sweater under my heavy leather jacket, and I am freezing my butt off.

The two monks walk along purposefully, as if they are going somewhere important, and even though I know it may be a bit disrespectful, I begin to follow them. I can hear the two of them talking in Tibetan and laughing among themselves as they walk along, and I wonder what it is that they find so funny. After a few blocks, they turn onto the very street I live on, stop at the café on the corner, and take a seat there at an outdoor table beside the canal.

Our apartment, where we taught many of the meditation classes, is only a couple of blocks away. The person who chose it did a great job, and managed to find an apartment in Amsterdam with a red beamed ceiling that was a dead ringer for the ceilings of Tibetan monasteries. When we had it fixed up, the walls covered with thangkas and Zazen posters, you could have just as easily been in the Himalayas as in an apartment on one of the oldest streets in Amsterdam.

A waiter comes out to take their order, and the monks each order a beer. For some reason, this just charms the socks off of me, and I walk up and ask whether I can join them. I know no Tibetan and only a few words in Dutch, and the monks know a little bit of Dutch and only two or three words in English, so getting this concept across to them is somewhat of a comedy of errors.

After a few aborted tries, frustrated, I curse under my breath in French, and the monks laugh and add a few choice words of their own in the same language. Then, using a pastiche of French, Dutch and English, I tried again to ask whether I could join them and they finally got the picture. They smiled warmly and gestured for me to sit down. I ordered a beer of my own.

What followed must have been hilarious to the Dutch bystanders. An American guy in a black leather jacket, trying to communicate with two Tibetan monks in traditional robes, using only the twenty or thirty words we had in common, in three different languages. Despite the challenge, we managed to have a good time with it, and laughed often as we tried to find out more about each other.

Using more sign language than spoken words, I finally got that they were here on their own, as travelers, not as part of any established sangha in the Netherlands. Strangely enough, given the difficulties of language involved, I was able to see that they were on a kind of sabbatical, trying to figure out whether the path they had chosen in their youth was still right for them. They were on a kind of walkabout, trying to figure out What To Do Next.

Touched, I showed them the posters I had been taking down, and after a few aborted tries managed to get across to them that I had been here for the last two weeks teaching Buddhist meditation, that the classes were now over, and that I was going through exactly the same crisis of faith they were. The shared silence that followed this mutual realization was quite profound. We sat there in that silence for a few minutes, staring out at the canal, listening to the music on the café's sound system, none of us knowing exactly what to say to each other, or in which language.

Just then, incongruously enough, the CD changed and over the sound system came the opening cut of one of my favorite albums. The song was Gram Parsons' Return of the Grievous Angel, and the country twang seemed remarkably out of place here in a sidewalk café on a 15th-century Dutch street, but it made me smile. Gram was one of my early music heroes. He was a hard-living, hard-drinking, no-holds-barred kinda guy, but he had a knack for harmony that was second to none. After his stints with the Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers, he struck off on his own, to explore with his protégé Emmylou Harris what he called high mountain harmony. The album playing on the sound system of the café, echoing in the narrow streets bordering the canal, was the high point of that exploration.

Despite myself, I began to sing along. I don't have that much of a voice, but Gram always sung in a key that was not too embarrassing for me, and I loved trying to add one more harmony line to his already-exquisite blending of voices. As I sat there singing quietly to myself, gazing out at the street, I suddenly noticed that mine was not the only new harmony part. Turning, I looked at the two monks and saw that they too were singing along. And they knew the words, every one of them.

They turned at the same time, looked at me in shock, and then erupted in laughter. What are the chances, after all, of three fans of an obscure 70s country-rock star running into each other in an Amsterdam café, especially when two of them are Tibetan monks? Go figure.

After

the laughter subsided, we continued to sing along with the album. It

was an interesting experience. The two monks sang using the double-note

throat singing practiced in Tibet, so in effect the three of us were

adding our own five-part harmony to each song. We wailed on the last

soaring notes of Grievous Angel, sang along sadly to Hearts

On Fire, rocked along with uptempo bar songs and country cry-in-your-beer

ballads, and finished up with a soulful rendition of the ultimate version

of Roy Orbison's Love Hurts.

After

the laughter subsided, we continued to sing along with the album. It

was an interesting experience. The two monks sang using the double-note

throat singing practiced in Tibet, so in effect the three of us were

adding our own five-part harmony to each song. We wailed on the last

soaring notes of Grievous Angel, sang along sadly to Hearts

On Fire, rocked along with uptempo bar songs and country cry-in-your-beer

ballads, and finished up with a soulful rendition of the ultimate version

of Roy Orbison's Love Hurts.

The bartender changed the CD at that point and our impromptu concert came to an end. To our surprise, the other patrons in the café, most of them Dutch, applauded and asked for more. The three of us sat there, somewhat embarrassed, not knowing exactly what to do. Finally, I went into the café and asked the bartender whether he would mind playing the last cut on the album for us. He agreed. I returned to the table and joined the monks in one last song. Sitting there in the fading light, we sang along with Gram and Emmylou words that each of us - each for our own reasons - could identify with:

In my hour of darkness

In my time of need

Oh Lord, grant me vision

Oh Lord, grant me speed

The song ended just as the sun set behind the houses across the street. The café crowd applauded again, the monks laughed heartily and slapped me on the back, and they stood up to leave. They managed to convey that they had somewhere they had to be. I glanced at my watch and realized that I had to be somewhere, too, back at the apartment preparing for one last group meditation before I left town. We shook hands, tried our best in three different languages to express how much fun it had been, and walked off along the canal, in different directions.

I never even knew their names. I don't know what became of them, or how their walkabout turned out. But it doesn't matter, or matter that we couldn't really communicate in words. What mattered was that, just for a moment, at sunset in a strange town, several monks ran into each other and found that they had more in common than they had any right to expect. We had things to share, things that all monks go through along the way, and for a short moment out of time, we were able to transcend them, smile, and instead of fighting the ups and downs, just sing along.

<< Back to

Ramalila.NET

![]() |

|![]() Also

visit Ramalila.COM

>>

Also

visit Ramalila.COM

>>